How often do law enforcement agencies use high-risk AI? Presidential advisers want answers

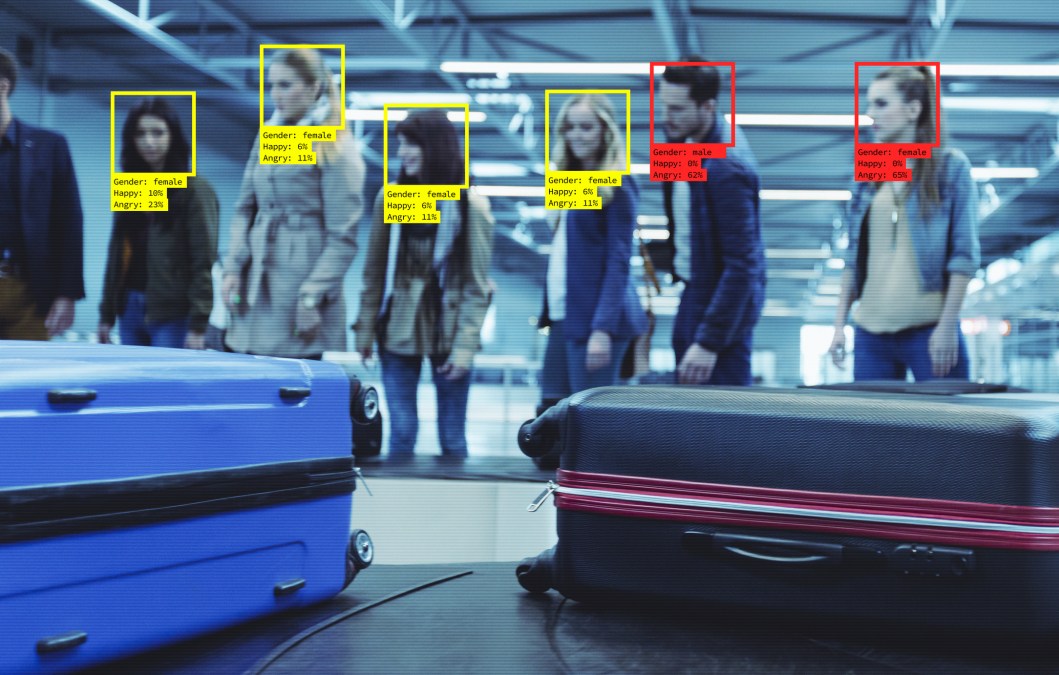

A visit with the Miami Police Department by a group of advisers to the president on artificial intelligence may ultimately inform how federal law enforcement agencies are required to report their use of facial recognition and other AI tools of that kind.

During a trip to South Florida earlier this year, Law Enforcement Subcommittee members on the National AI Advisory Committee asked MPD leaders how many times they used facial recognition software in a given year. The answer they got was “around 40.”

“That just really changes the impression, right? It’s not like everyone’s being tracked everywhere,” Jane Bambauer, NAIAC’s Law Enforcement Subcommittee chair and a University of Florida law professor, said in an interview with FedScoop. “On the other hand, we can imagine that there could be a technology that seems relatively low-risk, but based on how often it’s used … the public understanding of it should change.”

Based in part on that Miami fact-finding mission, Bambauer’s subcommittee on Thursday will recommend to the full NAIAC body that federal law enforcement agencies be required to create and publish yearly summary usage reports for safety- or rights-impacting AI. Those reports would be included in each agency’s AI use case inventory, in accordance with Office of Management and Budget guidance finalized in March.

Bambauer said NAIAC’s Law Enforcement Subcommittee, which also advises the White House’s National AI Initiative Office, came to the realization that simply listing certain types of AI tools in agency use case inventories “doesn’t tell us much about the scope” or the “quality of its use in a real-world way.”

“If we knew an agency, for example, was using facial recognition, some observers would speculate that it’s a fundamental shift into a sort of surveillance state, where our movements will be tracked everywhere we go,” Bambauer said. “And others said, ‘Well, no, it’s not to be used that often, only when the circumstances are consistent … with the use limitations.’”

The draft recommendation calls on federal law enforcement agencies to include in their annual usage reports a description of the technology and the number of times it has been used that year, as well as the purpose of the tool and how many people used it. The report would also include total annual costs for the tool and detail when it was used on behalf of other agencies.

The subcommittee had previously tabled discussions of the public summary reporting requirement for the use of high-risk AI, but after some refinement brought it back into conversation during an April 5 public meeting of the group.

Anthony Bak, head of AI at Palantir, said during that meeting that the goal of the recommendation was to make “the production” of those summary statistics a “very low lift for the agencies that are using AI.” Internal IT systems that track AI use cases within law enforcement agencies “should be able to produce these statistics very easily,” he added.

Beyond the recommendation’s topline takeaway on reporting the frequency of AI usage, Bak said the proposed rule would also provide law enforcement agencies with a “gut check for AI use case policy adherence.”

If an agency says they’re using an AI tool “only for certain kinds of crimes” and then they’re reporting for a “much broader category of crimes, you can check that very quickly and easily with these kinds of summary statistics,” Bak said.

Benji Hutchinson, a subcommittee member and chief revenue officer of Rank One Computing, said that from a commercial and technical perspective, it wouldn’t be an “overly complex task” to produce these summary reports. The challenges would come in coordination and standardization.

“Being able to make sure that we have a standard approach to how the systems are built and implemented is always the tough thing,” Hutchinson said. “Because there’s just so many layers to state and local and federal government and how they share their data. And there’s all sorts of different MOUs in place and challenges associated with that.”

The subcommittee seemingly aimed to address the standardization issue by noting in its draft that summary statistics “should include counts by type of case or investigation” according to definitions spelled out in the Uniform Crime Reporting Program’s National Incident-Based Reporting System. Data submitted to NIBRS — which includes victim details, known offenders, relationships between offenders and victims, arrestees, and property involved in crimes — would be paired with information on the source of the image and the person conducting the search.

The Law Enforcement Subcommittee plans to deliver two other recommendations to NAIAC members Thursday: The first is the promotion of a checklist for law enforcement agencies “to test the performance of an AI tool before it is fully adopted and integrated into normal use,” per a draft document, and the second encourages the federal government to invest in the development of statewide repositories of body-worn camera footage that can be accessed and analyzed by academic researchers.

Those recommendations serve as a continuation of the work that the Law Enforcement Subcommittee has prioritized this year. During February’s NAIAC meeting, Bambauer delivered recommendations to amend Federal CIO Council guidance on sensitive use case and common commercial product exclusions from agency inventories. Annual summary usage reports for safety- and rights-impacting AI align with an overarching goal to create more comprehensive use case inventories.

“We want to sort of prompt a public accounting of whether the use actually seems to be in line with expectations,” Bambauer said.