Direct File died under Trump. Meet the creators planning for its second life

In the weeks leading up to the Trump administration’s decision to kill Direct File, Merici Vinton held out a sliver of hope that the IRS’s free electronic filing tool would be spared.

After all, Elon Musk said repeatedly that the goal of his nascent DOGE project was to make government more efficient. What could be more emblematic of that mission, Vinton thought, than a government-built product to drastically simplify the filing process and save taxpayers untold amounts of time and money?

“At the beginning, I’ll say I took DOGE at their word,” recalled Vinton, a chief architect of Direct File. “I took them at their word in my head and hoped we had a shot.”

Two days after the end of the 2025 filing season, the Associated Press reported that the Trump administration planned to eliminate Direct File. For those waiting on a more official nail in the coffin, IRS Commissioner Billy Long buoyantly swung the hammer last month during an appearance at the National Association of Enrolled Agents Tax Summit.

“You’ve heard of Direct File,” said Long, who was removed from his role days later. “That’s gone. Big beautiful Billy wiped that out.”

By the time Long made those comments, Vinton and other key players involved in Direct File’s creation were out of government, left to grapple from the outside with the reality that their first-of-its-kind, user-praised digital initiative was unceremoniously dumped before most taxpayers ever got the chance to use it.

“Not a lot of people get to see the birth and the death of something they bring to life in government,” Vinton mused.

For Direct File alums, there’s not really a silver lining to be found in the program’s demise after just two limited tax filing seasons. But in its wake, a small group of tech and policy experts who helped build the tool have found a new purpose: keeping the free-filing dream alive as Future of Tax Filing fellows with the nonprofit Economic Security Project.

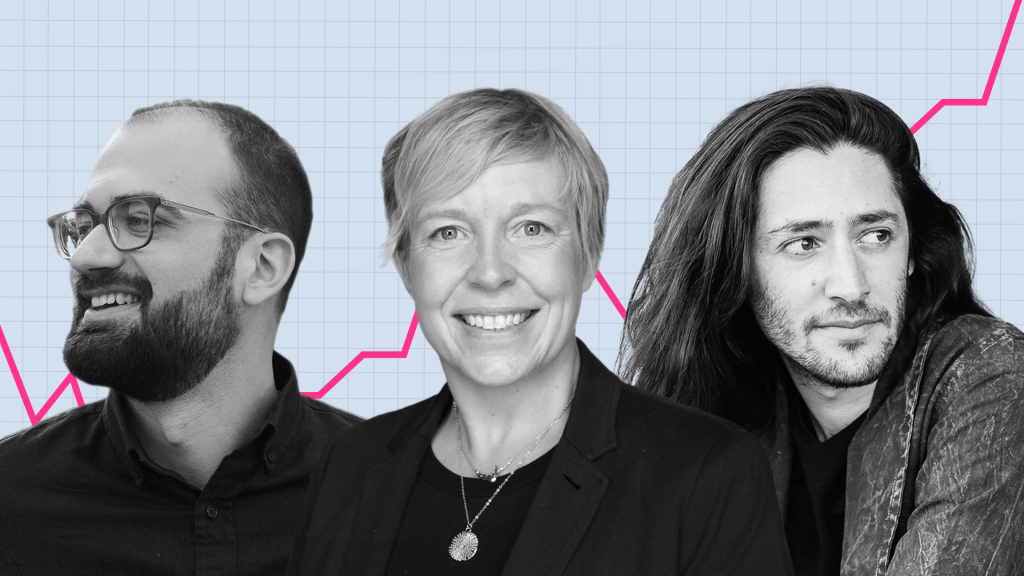

Vinton, former Code for America program director Gabriel Zucker, and ex-IRS product and design gurus Chris Given and Jen Thomas began their fellowships in May, kicking things off by documenting everything they could on Direct File to plant the seeds for a revival under a different administration. They’ve also put their heads together on how to build new civic tech tools aimed at easing the filing process and helping taxpayers identify credits they may be missing out on.

“It was four years of really nonstop work on one thing or another,” said Zucker, who helped develop the Direct File companion FileYourStateTaxes at Code for America. “It seemed like really the right moment to reflect on all that, see what lessons we’ve learned, and try to take stock and document a lot of that for the future before running at the next thing. And that’s really what we’re doing.”

For the tax-filing fellows, taking stock has often meant looking back a bit further to how they ended up in government, and why those early career choices led them to keep fighting for a public service stopped agonizingly short of the goal line.

Before the right place, right time

About 30 miles south of a town called Gordon in far northwest Nebraska, Vinton grew up on a ranch, rode a horse to her one-room schoolhouse and had a front-row seat to local government at work.

There wasn’t a lot going on in her tiny community. But if the roads needed fixing or there were issues with the water system, a “very engaged” public sprung to action and problems got solved. “We had to create committees and understand the politics to make sure … everyone was taken care of and able to get what they needed,” she said.

That civic-minded upbringing led Vinton to tech and public engagement roles with the 2008 Obama campaign, the Sunlight Foundation and the organization that became AmeriCorps. Those jobs laid the groundwork for her hiring in 2010 as the first employee of the fledgling Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s technology team.

The rookie CFPB technologists quickly committed to a GitHub-as-gospel philosophy, working exclusively in open source to align with the agency’s foundational, pro-transparency principles. Building the CFPB’s consumer complaint database was a particular highlight for Vinton, an experience that forced her to really think about how digital government operations could be a force for good.

Zucker reached a similar conclusion, though his origin story couldn’t have been more different. A New York City native and acclaimed pianist and composer, Zucker graduated summa cum laude from Yale, where he led the university’s Hunger and Homelessness Action Project and wrote his thesis on public employment programs in the U.S.

Postgrad work with the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab and the Connecticut Heroes Project paved the way for Zucker’s move to Oxford to study applied statistics, where he focused on the targeting of government employment programs.

“I love having a stats background, because I think it helps you think about the world in a quantitative way,” he said. “It’s very valuable for understanding what kinds of policies, what kinds of interventions are actually going to be valuable in benchmarking success for all kinds of things.”

A nearly three-year stint with U.S. Digital Service followed, giving the newly minted Rhodes Scholar a chance to add technical skills to his policy and stats-focused portfolio. Being farmed out to different federal agencies and observing what technology processes weren’t working was an eye opener for Zucker — but serving during the first Trump administration left him feeling a sense of unfinished business.

“Individual people rarely are in the right system to contribute. And while I learned a lot … at USDS, I don’t think I was in the right place at the right time,” he said.

As Zucker plotted his exit from the federal government, Given — the eventual Direct File product lead — was fully settled in. A graduate of Bard College in upstate New York with roots in southern Maryland, State College, Pa., and Maine, Given’s pre-Direct File claim to fame was working with 10 federal agencies via USDS and three states.

His undergraduate studies in international relations didn’t necessarily portend big technical feats, but a job in education technology and a fortuitous decision to volunteer with Code for America’s D.C. brigade led to nonprofit tech work and then a position with “what was hoped to be the D.C. Digital Service.”

“I was the first hire and also the last hire. It did not go well,” Given quipped. “But from there, I wanted to join the U.S. Digital Service to kind of see how the professionals did it.”

Once entrenched at USDS, Given embarked on his 10-agency odyssey, which included stops at the Social Security Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the IRS.

As a detailee at the tax agency in 2021, Given focused on Child Tax Credit provisions as part of the implementation of the American Rescue Plan and represented USDS in the Direct File interagency policy process. In his spare time, he worked with United Way’s Volunteer Income Tax Assistance program, burnishing his tax knowledge along the way.

At that point, Vinton was back in the federal government after a post-CFPB jaunt to London for almost a decade, leading the Child Tax Credit implementation work out of the White House and poised to take over as deputy service owner of Direct File. In late 2022, Given was officially tapped to lead the team charged with designing and building the technology.

With that, the sprint to launch the free electronic filing tool was on.

Building ‘the holy grail’

If there was a shadow hanging over the Direct File team as it embarked on its mission, it was the ghost of healthcare.gov and its ill-fated 2013 launch. Vinton was working in the U.K. during the universally panned rollout of the website for Affordable Care Act plan sign-ups, but she worried that the fallout from it would be “a bunch of lawyers [getting] into a room” and preventing the actual policymakers and tech wizards from working their magic.

“We have to be side by side, together,” she thought at the time. “We wanted to increase people’s expectations of government. We wanted to set the standard higher, but also regain confidence after healthcare.gov [and show people] that government can do this stuff.”

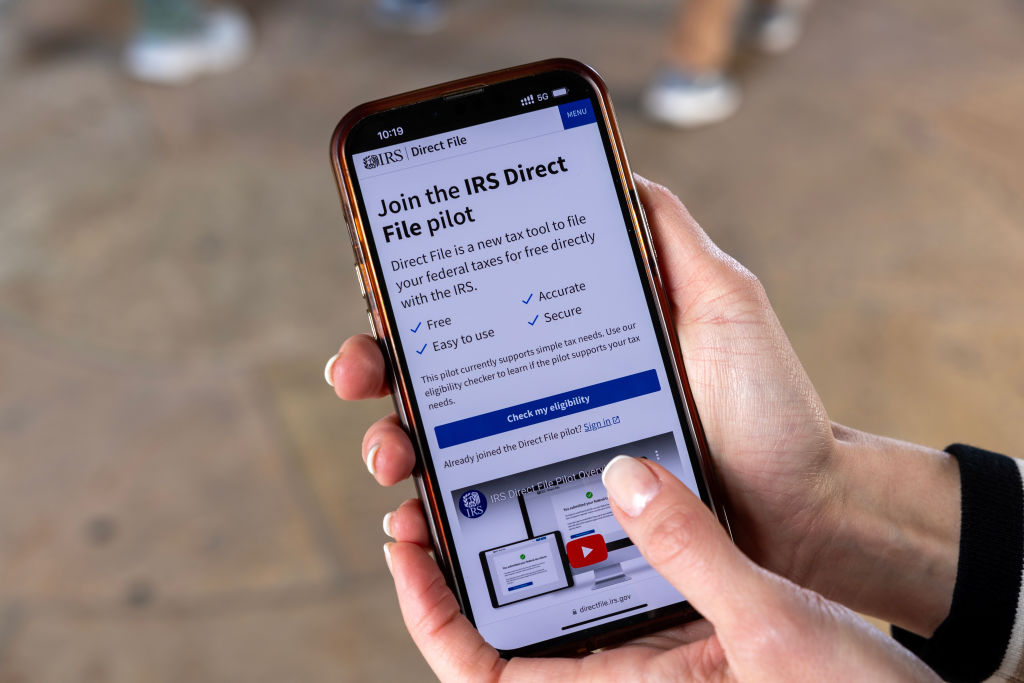

The major challenges in Given’s view were staffing and scaling up. When work on Direct File began in earnest, there were just seven people on board. When the tool shipped for the 2024 filing season for taxpayers in 12 states, there were 75 people on Given’s product team alone, consisting of engineers, designers and data scientists. “We had a whole raft of skill sets in there,” he said.

That team was charged with building a product that translated the incredibly dense U.S. tax code into machine code concepts, and having designers — following detailed conversations with lawyers in the IRS’s Office of Chief Counsel — be able to produce an intuitive presentation on the page.

Jen Thomas, who declined to be interviewed following the completion of her Future of Tax Filing fellowship in July, was the person who made that design miracle happen, according to Given.

“I described people needing to learn taxes. Jen took to taxes like a fish to water,” he said. From dealing with lawyers to seamlessly converting tax code to a digital interface to building a team of talented, like-minded designers, Thomas was “hugely influential to the design of Direct File” and the user-friendly accolades it would soon receive, Given added.

Building an aesthetically pleasing, instinctual product was all well and good, but there was still the issue of creating a parallel structure for state tax filing. The Direct File team had to foster partnerships with state governments and create what would become a state API solution.

Overcoming that “existential challenge” was a massive victory for Given’s team, especially when taking into account previous state-level efforts with products that were “consistently underutilized because they didn’t file federal returns,” he said.

That’s where Zucker and his Code for America cohorts came into play. That org, which Zucker joined in 2021, had also gotten its tax-filing feet wet around that time with the implementation of the Child Tax Credit. A report to Congress as part of the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act called for a study into an IRS-run free tax filing system, and Code for America was quickly on board from the outside, figuring out how to make things work for the states.

“An easy-to-use filing tool was always kind of the holy grail,” Zucker said. “Not that we solve every problem in filing, but you can’t really picture solving the filing system without that. You kind of need that in order to get to the next step.”

The result of those efforts was the standing up of a product fully integrated with Direct File, rolled out by Code for America to taxpayers in Arizona and New York for the 2024 filing season, plus Idaho, Maryland, New Jersey and North Carolina in 2025. FileYourStateTaxes users were presented with a seamless way to import federal data and answer just a couple of questions to finish their state returns.

Making the process even simpler was a monumental achievement over at the IRS: As part of Direct File’s 2025 expansion to 25 states, Given’s team figured out how to pre-populate users’ data from the previous year’s return.

“Frankly, I didn’t think we’d be able to pull that off until 2026,” Given said. “It was quite the effort by the data import team to actually pull those pieces together and get it in place where we could not only try it out with a few taxpayers, but literally roll it out to everybody in 2025.

“And then, yeah. It very quickly ended after that,” he added. “Frankly, I still have not totally processed that.”

Dealing with a ‘dark’ place

The end of Direct File didn’t exactly come as a surprise. Adam Ruben, vice president of campaigns and political strategy at the Economic Security Project and a day-one champion of Direct File, said raising awareness about the tool was “much more challenging this year because the administration … [was] actively sabotaging the outreach efforts.”

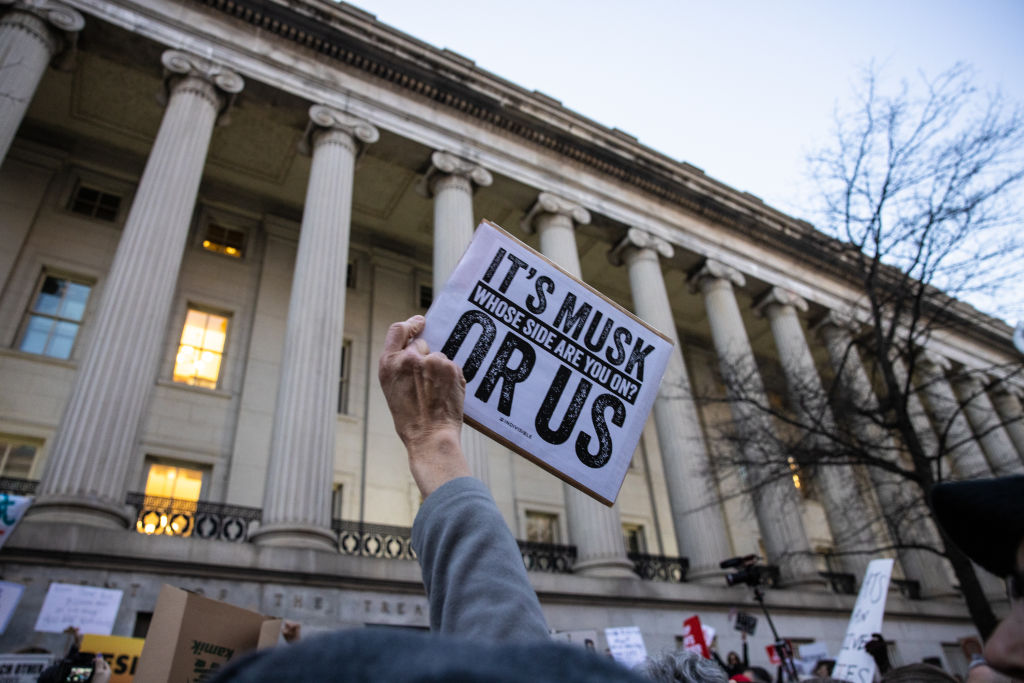

In early February, Musk highlighted a post on X from a blue-check account that criticized the General Services Administration’s 18F tech services team and Direct File. The world’s richest man quote-tweeted that post, saying “That group has been deleted” — without specifying whether he was referring to 18F or Direct File.

Less than a month later, 18F was shuttered. Direct File survived the tax season, but in Ruben’s mind, the damage was done and symbolic of the administration’s attempt to bury the product.

“Of course, [Musk’s tweet] wasn’t true,” Ruben said. “But if you look at the Google search trends, the single biggest day of searches ever for Direct File was [that] day, [and] it was misinformation.”

The IRS did not respond to a request for comment.

Fending off near-constant threats from congressional Republicans to stop Direct File in its tracks and a sustained lobbying campaign against the tool by the tax preparation and software industry was tough enough to stomach. But the finality of it all — combined with the administration’s simultaneous decimation of the federal workforce — left the Direct File makers in what Vinton described as a “dark” place.

“I think I was in shock with a number of things, but yeah, it was a couple days later where it really hit me, and I became really angry and frustrated,” she said. “It’s a thing people love, it’s done, just let it go.”

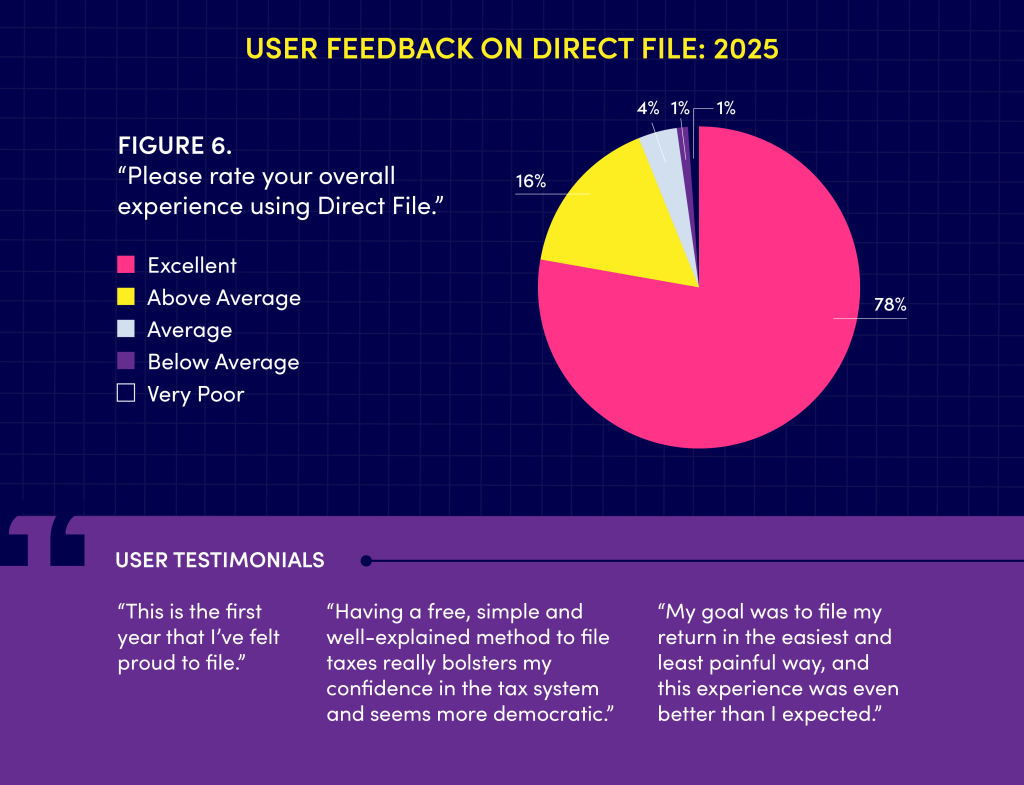

Calling Direct File a beloved customer product wasn’t just creator bias; the Center for Taxpayer Rights obtained the IRS’s 2025 filing season report and found that 94% of taxpayers rated their experience with the tool as “excellent” or “above average,” an uptick from the 90% who said the same in 2024. The product’s net promoter score, which market researchers use to measure customer satisfaction on a scale of -100 to +100, jumped from +74 to +80 over the same period.

“By comparison, industry-leading private tax prep software has an NPS of +52; a score of +80 tops nearly every company in the country, across all industries,” the Center for Taxpayer Rights noted.

The positive customer reviews were no surprise to Ruben — nor were the report’s findings that taxpayers showed “significant interest in Direct File” but also were largely unaware of its existence. The upside for expansion was undeniably there, but only with an administration that had the appetite for it — or an outside group prepared to pick up the baton.

Ruben, who previously led the Economic Security Project’s Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit work, had known Vinton for years and worked closely with Zucker on Direct File promotion. He later met Given at a happy hour celebrating the pilot program in 2024 and was eventually told that Thomas was “one of the key players behind the scenes who made Direct File happen.”

Assembling the four Future of Tax Filing fellows wasn’t quite the team-building exercise you might see in a heist movie — “I think we probably did not have the pulsing soundtrack during recruitment conversations and it was less of a montage,” Ruben joked — but the result was the same: A motivated group of people with complementary skillsets brought together by one fundamental purpose.

“How can we try,” Ruben said, “to keep some of this alive?”

Continuing Direct File ‘in spirit’

The first step for the fellows was an obvious one: Collect every piece of information they had about Direct File and do a full download on what decisions were made and why — “the kind of thing that you would only know if you’ve been in the room,” Ruben said.

That retrospective was happening at the same time as the IRS was releasing the vast majority of Direct File’s code on GitHub, living up to its requirements as part of the SHARE IT Act. Given always believed that as a taxpayer-funded product, Direct File had to be open source.

“Ultimately, by putting this out there, we were saying anyone can inspect this. ‘We think we are getting you the best refund, you’re entitled to check our work,’” he said.

With the technical components accounted for, a blueprint for Direct File 2.0 was out in the open for everyone to see. Documenting lessons learned would become similarly important; Ruben said the No. 1 goal has been to leave a “playbook for a future team” behind, so it’s critical that the Direct File alums answer questions on everything from what expansions should be prioritized to what pitfalls must be avoided.

The North Star for the fellows is how “to make it easier for Direct File to come back someday,” Given said. In thrice-weekly virtual check-ins, they’ll discuss other strategies and objectives and then go about their work separately.

For Given, that means working with states more closely to help them “continue Direct File in spirit.” He’s hopeful that the fellows’ work with the Economic Security Project continues to “build trust” through better digital experiences, including raising awareness for taxpayers about various credits to which they’re entitled.

Vinton, meanwhile, has approached the fellowship as an opportunity to focus “more on the policy side” and lean into the forward-looking element of ESP’s remit. Beyond laying the groundwork for a resurrection of Direct File, she has relished the chance to dig into “more futuristic thinking” about tax services.

“It’s super fun and way out of my lane, intimidating,” she said. “But I’m enjoying it. And Gabe and Chris are a lot of fun to work with on that.”

There are some specific improvements to Direct File that Zucker said he has in mind, though he’s not ready to share those tweaks just yet. But he’s found great value in comparing notes with his colleagues, brainstorming ways to push beyond the free-filing tool and exploring other pieces of the tax system that might benefit from a technological boost.

With their time at the Economic Security Project set to wrap in the fall, the Future of Tax Filing fellows are thinking not just about what’s next for tax services, but also the legacy they’ve left with Direct File.

If Zucker has his way, what the team accomplished with the product will serve as “inspiration” for other govtech innovations that hold similar ambitions.

“I hope that [future administrations] pick the tax work back up where it was, which was a lot of momentum. And I hope they take that same energy across the rest of the government,” Zucker said. “I’m a firm believer, government can be a force for good in people’s lives. And I think this is a powerful example of how that was playing out.”