Is artificial intelligence a threat? Experts weigh the risks

A panel of artificial intelligence experts balked at the idea that we could wake up tomorrow in a post-apocalyptic, Terminator-like world where super intelligent machines are threatening humanity.

Nonetheless, several participants in a discussion held by the Washington, D.C.-based Information Technology and Innovation Foundation this week said it’s critical to weigh the risks and opportunities that developing “AI” presents.

“The call to action is not, ‘Stop doing AI.’ It’s not doom,” said Nate Soares, executive director of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute. “It’s we have thousands of person-years and billions of dollars every year going into increasing capabilities and very little time spent on” how to get those machines to conform with humanity’s goals.

In recent months, several tech leaders have signaled concerns about the potential of highly intelligent computers threatening people in the future. Among them is SpaceX mogul Elon Musk, who this week gave $7 million to researchers exploring the risks of AI. Last year, he told CNBC there’s a “potentially dangerous outcome with artificial intelligence.”

During the ITIF discussion, several panelists advocated thinking about these future dangers before they become more immediate threats. That way, researchers can change course if their work is headed down an undesirable path, said Stuart J. Russell, electrical engineering and computer sciences professor at University of California, Berkeley.

“We choose what it’s going to be. Whether or not AI will be a threat to the human race depends on whether or not we make it a threat,” Russell said.

Russell compared AI to climate change or the development of nuclear weapons, problems created as a result of innovation. There’s a tipping point where the negative consequences become irreversible, he said.

Ronald Arkin, a professor and associate dean for research and space planning in the College of Computing at Georgia Tech, said not all researchers have altruistic intentions, and it’s important to develop policies that would lessen the threats in the future.

“You cannot leave this up to the AI researchers. You cannot leave this to the roboticists. We are an arrogant crew. We think we know what’s best and how we can do it. But we need help,” he said.

He said researchers, policymakers and others need to work together to find ways to make the future of AI safer and help it provide a greater benefit to humanity.

He added, “If we don’t do that, then we ignore that at our own peril.”

Speaking to FedScoop after the discussion, Arkin suggested that AI researchers who apply for National Science Foundation grants include an explanation of the social implications of their technology as part of the review process.

“That’s to be in no ways limiting” and would not be reviewed by an ethics panel, he said. It “would help them come to grips with their own trajectories with the technologies that they’re creating.”

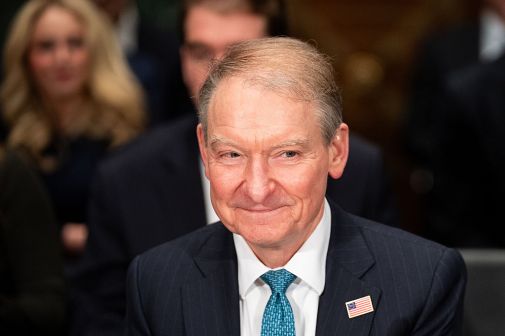

Meanwhile during the panel, Robert Atkinson, ITIF’s president, accused some of the panelists of advocating Luddism. He said that artificial intelligence had the potential to alleviate major societal problems, like world hunger. “But if we talk about it in these apocalyptical terms, it could turn it in the other direction,” he said.

Manuela Veloso, a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, was less optimistic than other panelists that artificial intelligence was on the horizon. Right now, researchers can make computers very good at specific tasks — like playing chess — but they probably can’t do much else, she said.

“I don’t think that concept — the integration of all the capabilities … like natural language, planning — is within the future,” she said.

But she said humans would advance as technology does, and she lamented the idea of putting limits on human innovation. Every new form of technology, from cell phone texting to a hair dryer, poses some risks, she said.

“What in our minds exists that eventually does not have some danger?” Veloso asked.