HHS’s reported AI uses soar, including pilots to address staff ‘shortage’

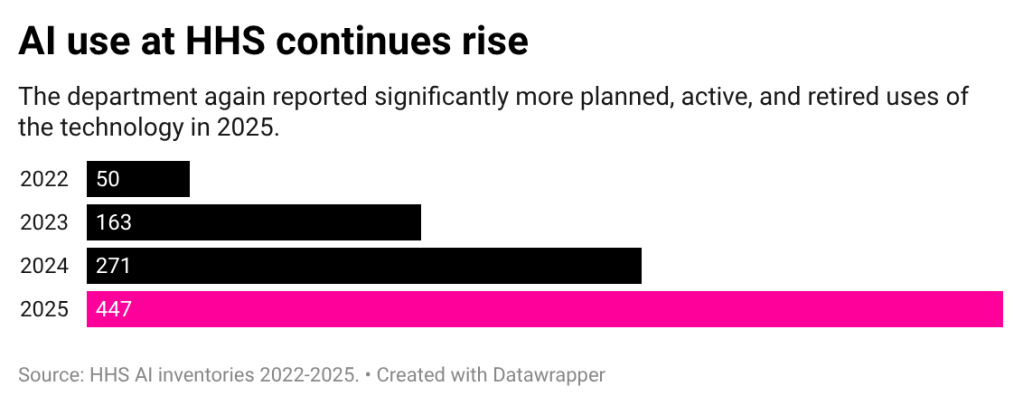

Reported uses of AI increased by 65% at the Department of Health and Human Services in 2025, according to the agency’s latest inventory, indicating even more widespread use of the technology as leadership simultaneously moved to reduce the workforce.

New use cases included pilots aimed at alleviating staffing shortages, multiple disclosures of so-called “agentic” tools, and an additional deployment for data related to the department’s work with unaccompanied children. Over half of the uses for 2025 are in pre-deployment or pilot phases, which means most of the applications are just getting started.

Valerie Wirtschafter, a Brookings Institution fellow focused on artificial intelligence and emerging technology, said her read on the inventory is that “there’s been a huge focus” on expansion at the agency. And HHS was already among the agencies with larger use case inventories in years past.

They’re “leaning into it,” Wirtschafter said.

The uptick in uses at HHS follows years of dramatic jumps in the health and human services agency’s reported uses of the technology. In 2023, the department’s inventory more than tripled from the previous year, and in 2024, it reported a 66% surge. The latest increase, of course, is set to the backdrop of significant change at the department and an aim by HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to do “a lot more with less.”

Over the past year, the department moved to restructure bureaus and fire thousands of employees, in line with the Trump administration’s calls for agencies to reduce their footprint. At least two use cases specifically address a limited workforce as a reason for the tool.

The Office for Civil Rights disclosed pilots using both ChatGPT and Outlook CoPilot to address the problem of “staffing shortages.” ChatGPT is used for efficiency in investigations “to break down complex legal concepts in plain language and identify patterns in court [rulings] impacting Medicaid services.” Meanwhile, CoPilot is used via Westlaw for “faster correspondence with public.”

According to the inventory, both of those uses were for “law enforcement.” Neither entry included details about how specifically the generative tools were addressing workforce shortages.

HHS and OCR did not respond to FedScoop’s requests for comment to further explain some of the uses and provide additional details not included in the publication. FedScoop submitted a request through HHS’s email form last week and followed up with spokespeople directly on Tuesday. FedScoop also submitted an inquiry through OCR’s own email form on Wednesday.

While it’s hard to tell exactly what staffing issues OCR might be addressing and how, some generally cautioned against any uses meant to replace — rather than assist — workers.

“AI can be an important tool in any number of professions, and it can certainly have the potential to make government better and more efficient for citizens and all people,” said Cody Venzke, a senior policy counsel in the ACLU’s National Political Advocacy Department who is focused on surveillance, privacy, and technology.

That said, Venzke added: “It is not a stand in for all human decision making, and that is especially true when you are committed to breakneck downsizing of the federal government.”

Wirtschafter similarly noted that the need for uses aimed at addressing staffing shortages “seems to be a little bit of a problem, maybe of their own making.”

But Wirtschafter applauded the fact that the inventory is what provides the public with transparency into interesting uses like those at OCR. “Part of the fact that they have provided this transparency is that you can see, sort of, the problems that are attempting to be solved,” she said.

Agentic uses, Palantir, xAI

Among the other notable use cases, the Administration for Children and Families disclosed that it’s planning to use an AI system to verify identities of adults applying to sponsor unaccompanied minors in the care of its Office of Refugee Resettlement.

That use case is currently in the pre-deployment phase but is one of the department’s few “high-impact” entries, which are uses that will need to adhere to additional risk management practices to continue operating. It does not disclose the vendor.

Other tools seemed aligned with the Trump administration’s political goals. ACF disclosed that it had deployed two tools to identify position description and grants that run afoul of the president’s executive orders aimed at erasing diversity, equity, and inclusion from the federal government.

Those use cases both list Palantir as a vendor and cite “increased efficiency of review, with reduced administrative burden on staff” as reasons for the tool. Palantir — which has attracted attention for its work with Immigration and Customs Enforcement during the Trump administration — is a frequently listed vendor in HHS’s inventory, with more than 15 use cases attributed to the tech company. The majority of those use cases are within ACF.

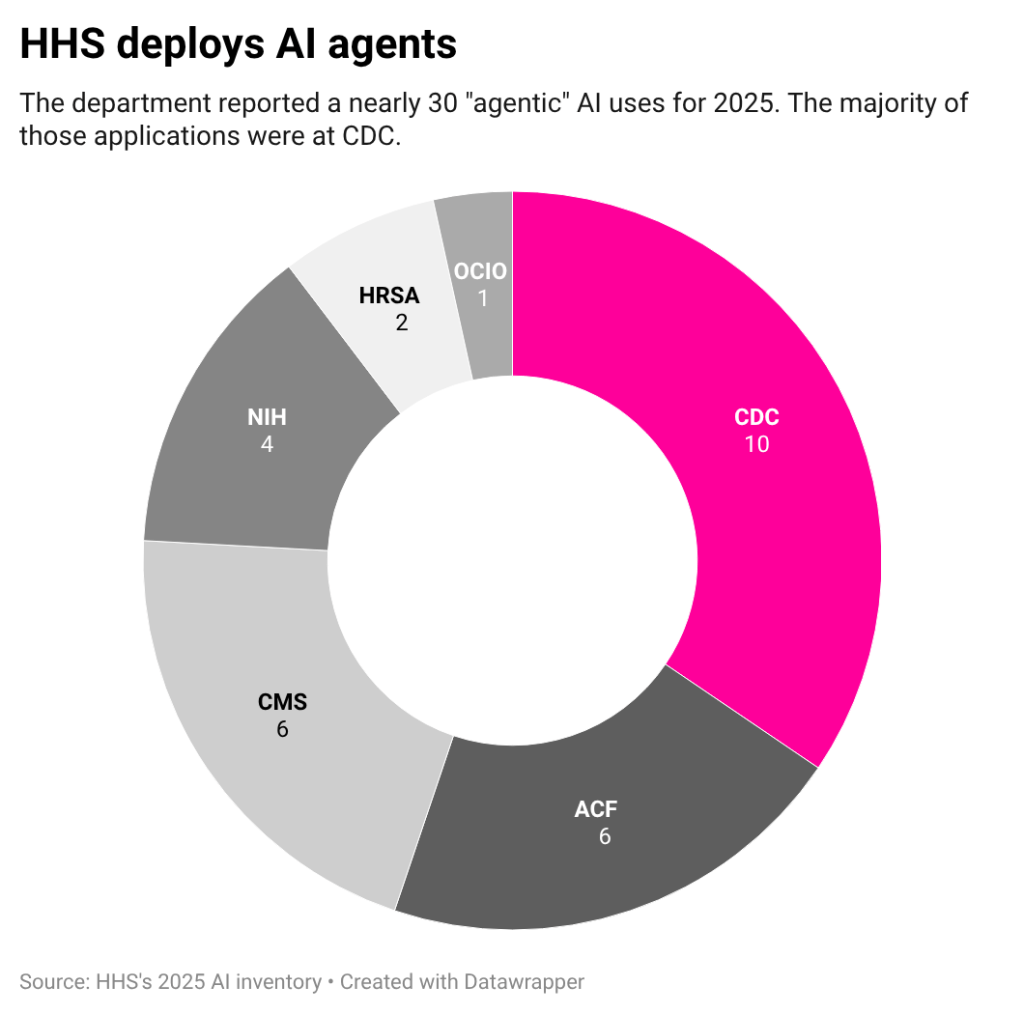

Additionally, HHS lists multiple “agentic” AI uses for 2025.

Agentic AI is a commercially buzzy application of the technology in which specific tasks are performed autonomously or with little human intervention. While those use cases are still just a small portion of HHS’s inventory, last year there were only a handful use cases called AI agents across the entire federal government.

One of those entries is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pilot of OpenAI’s Deep Research. According to the disclosure, the tool is being used to help the agency process large volumes of research and data, producing report-style outputs. The entry references an internal study that found “94% of prompts resulted in successful, high-quality reports” and that most of those were completed within 30 minutes.

Other uses included an agent for Freedom of Information Act responses at Health Resources and Services Administration and an internal use case for staff questions about ethics policies at the National Institutes of Health. Both of those were pre-deployment.

Not included in the inventory: HHS’s use of xAI’s Grok as part of its recent RealFood.gov website rollout. The website, which encourages Americans to “eat real food” rather than processed food, is in line with the agency’s new dietary guidance. The page directs users to use AI to answer their health questions and links directly to Grok.

While that use of the Elon Musk-affiliated AI chatbot isn’t on the inventory, the agency did list “xAI gov” as one the services it uses for generating document first drafts and other communications, as well as for scheduling and managing social media posts. Both of those use cases were listed on a separate inventory of common commercial applications of the technology.

Room for improvement

Compared to other inventories, Wirtschafter said HHS’s publication is among the more detailed submitted by agencies for 2025 in terms of information about each use and the problems it aims to fix.

But that doesn’t mean the publication is perfect. The lack of high-impact use cases on HHS’s inventory, for example, has raised questions among advocates and researchers looking into the disclosures.

The new inventory is also difficult to compare year over year. Unlike last year’s inventory or many other inventories published this year, HHS’s new publication does not have unique identifiers for each entry. Those identifiers are generally an alphanumeric code the agency designates for each use, and without them, it’s difficult to identify new tools, particularly if the name or other details have changed.

And blank fields also leave advocates wanting more.

“Reviewing the inventories raises serious questions about the amount of transparency that is actually being provided here, because there are many, many fields that are left blank or simply are noted to be sensitive information, not for public disclosure,” Venzke said.

Specifically, Venzke pointed to the absence of public privacy impact assessments for the overwhelming majority of use cases.

Out of all of the submissions in HHS’s inventory, just one indicated where the privacy impact assessment was located. Despite being on the guidance sent to agencies by the White House Office of Management and Budget, some agencies did not include the category at all. While HHS did include it, it provides little to no information about how the agency has assessed privacy, if at all.

Agencies, by statute, are required to conduct privacy impact assessments (PIAs) for technologies that collect personally identifiable information to ensure those systems are equipped to protect that information. Those assessments are then required to be publicly accessible.

But finding public privacy impact assessments is often difficult, in part because systems can use different names and the assessments can cover multiple systems, Venzke explained. “Even just a link to the PIA provides a lot more surety for holding the government accountable,” he said.

HHS either provided no link, said the PIA was forthcoming, or said the PIA wasn’t publicly available. Venzke said that “defies the entire point of having a PIA, which is public transparency.”

For Quinn Anex-Ries, a senior policy analyst at the Center for Democracy and Technology’s equity in civic technology team, the spike in inventory size prompts questions about what the agency is doing to manage it.

“The thing that’s worth paying attention to most is, what, if anything, the agency is saying or doing to account for the fact that their total AI use has increased by such a significant degree,” Anex-Ries said. “When we look to places like their AI compliance plan and AI strategy, it’s not really clear that they did a bunch of additional groundwork to prepare the agency for their AI use to grow by such a huge margin.”