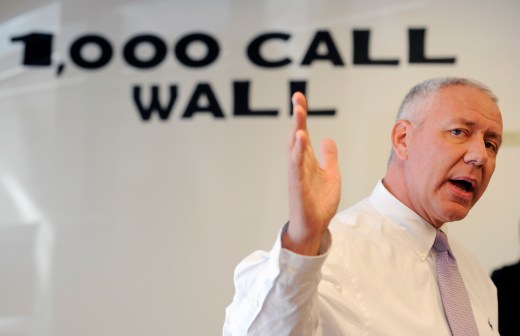

FedScoop’s Dan Verton (r) talks to James Burch (l), the Pentagon’s deputy inspector general for investigations. (Photo: Kyle Richardson, DOD IG)

FedScoop’s Dan Verton (r) talks to James Burch (l), the Pentagon’s deputy inspector general for investigations. (Photo: Kyle Richardson, DOD IG)The U.S. Navy this week announced a sixth officer has been implicated in a widening bribery scandal involving a foreign defense contractor.

The investigation by the Defense Criminal Investigative Service and other federal law enforcement agencies is looking into allegations that Leonard Glenn Francis, the chairman of Glenn Defense Marine Co., known by his nickname “Fat Leonard,” bribed the Navy officers with prostitutes, luxury travel and large amounts of cash in exchange for classified and internal information that could favor his business. Three officers have been arrested so far.

News of the widening scandal comes as the Pentagon faces tough new questions about its financial auditing system – questions that paint a picture of a Defense Department acquisition system that despite sequestration remains flush with cash, overly dependent on private contractors and is ripe for abuse.

But James Burch, the Pentagon’s deputy inspector general for investigations and the head of the Defense Criminal Investigative Service, isn’t particularly surprised or concerned about the number of fraud cases. In an exclusive interview with FedScoop, Burch acknowledged larger, systemic problems may be playing a role in the number and types of crimes the department has to deal with, but they don’t tell the whole story.

“People are stealing,” Burch said. “It’s that simple. Whether it’s DOD or a bank robber, people are stealing trying to get something for nothing.”

According to Burch, procurement fraud is what keeps his investigators busy. He oversees a global force of 350 investigators who are currently working 1,700 open cases involving procurement fraud, health care fraud, illegal technology transfer and cyber-crime.

“Change is really the only constant,” Burch said. “You have to always be leaning forward looking for the new methods [people use] to steal money. How are the bad guys doing it, where are they doing it, why are they doing it there and are we adjusting to those trends?”

But the power of DCIS also comes from its status as a component of the DOD’s IG office, Burch said. It’s rare DCIS can work a case and determine a clear reason behind why certain people are committing particular crimes and why they succeeded. Those conclusions almost always come from a larger IG view of the system and its shortcomings, he said.

“The information that we develop during our investigations doesn’t stop here. It has to be part of the bigger OIG trends and analysis” of people, groups, contracts and organizations, Burch said. “But the end product has to be a story” put into a format that can be used by other components of OIG to help improve the DOD enterprise, he said.

Technology has helped DCIS improve its workflow, but it’s also made investigations more difficult. Most crimes today, especially those involving fraud, involve a digital footprint, Burch said. And that means mountains of additional evidence through which investigators must search.

“That is really hard to do,” Burch said. “You have so much information and you have to put it in a form to be able to search it in a reasonable amount of time.”

The answer to the data overload problem is a DCIS headquarters initiative that brings computing power to bear in one central location to help field agents search and analyze the volumes of digital evidence.

“We can uniformly help our field agents and actually put more hours in their day from an analytical perspective,” Burch said.

Despite the digital footprints today’s criminals often leave behind, it is the fundamental aspects of the crimes that have not changed, according to Burch.

“Sometimes, you’ll come across coalitions of people,” he said. “Usually, it’s representatives of companies coming together to try to fix prices or eliminate [competitors]. But most of our efforts usually come down to people. Sometimes, you’ll find a systemic issue where there’s a weakness. But sometimes, it’s people just lying, stealing and cheating.”