Post-quantum cryptography experts brace for long transition despite White House deadlines

The White House’s aggressive deadlines for agencies to develop post-quantum cryptography strategies make the U.S. the global leader on protection, but the transition will take at least a decade, experts say.

Canada led the Western world in considering a switch to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) prior to the Office of Management and Budget issuing its benchmark-setting memo on Nov. 18, which has agencies running to next-generation encryption companies with questions about next steps.

The memo gives agencies until May 4, 2023, to submit their first cryptographic system inventories identifying vulnerable systems, but they’ll find the number of systems reliant on public-key encryption — which experts predict forthcoming quantum computers will crack with ease — is in the hundreds or thousands. Agencies, software, servers and switches often have their own cryptography, and agencies don’t necessarily have the technical expertise on staff to understand the underlying math.

“This will be the largest upgrade cycle in all human history because every single device, 27 billion devices, every network and communication needs to upgrade to post-quantum resilience,” Skip Sanzeri, chief operating officer at quantum security-as-a-service company QuSecure, told FedScoop. “So it’s a massive upgrade, and we have to do it because these quantum systems should be online — we don’t know exactly when — but early estimates are three, four years for something strong enough.”

Bearish projections have the first quantum computer going live in about a decade, or never, with scientists still debating what the definition of a qubit — the quantum mechanical analogue to a bit — should even be.

QuSecure launched three years ago but became the first company to deploy PQC for the government this summer, when it proved to the U.S. Northern Command and North American Aerospace Defense Command that it could create a quantum channel for secure aerospace data transmissions at the Catalyst Campus in Colorado Springs, Colorado. The company used the CRYSTALS-KYBER cryptographic algorithm, one of four the National Institute of Standards and Technology announced it would standardize, but a quantum computer doesn’t yet exist to truly test the security.

The first quantum security-as-a-service company to be awarded a Phase III contract by the Small Business Innovation Research program, QuSecure can contract with all federal agencies immediately. Customers already include the Army, Navy, Marines and Air Force, and the State, Agriculture, Treasury and Justice departments have inquired about services, Sanzeri said.

QuSecure isn’t alone.

“We are having discussions right now with various federal agencies around what they should be doing, what they can be doing, in order to start today — whether it’s in building out the network architecture or looking at Internet of Things devices that are being sent into the field,” said Kaniah Konkoly-Thege, chief legal officer and senior vice president of government relations at Quantinuum, in an interview.

Defense and intelligence agencies are better funded and more familiar with classified programs requiring encryption services and therefore “probably in a much better position” to transition to PQC, Konkoly-Thege said.

Having served in the departments of the Interior and Energy, Konkoly-Thege said she’s “concerned” other agencies may struggle with migration.

“There are a lot of federal agencies that are underfunded and don’t have the resources, either in people or funding, to come and do what’s necessary,” she said. “And yet those agencies hold very important information.”

That information is already being exfiltrated in cyberattacks like the Office of Personnel Management hack in 2015, in which China aims to harvest now, decrypt later (HNDL) data with fully realized quantum computers.

Post-Quantum CEO Andersen Cheng coined the term, and his company’s joint NTS-KEM error-correcting code is in Round 4 of NIST’s PQC algorithm competition.

Cheng points to the fact he could trademark his company’s name as proof PQC wasn’t being taken seriously even in 2015 and certainly not the year prior, when he and two colleagues were the first to get a PQC algorithm to work in a real-world situation: a WhatsApp messaging application downloadable from the app store.

They took it down within 12 months.

“One of my friends in the intelligence world called me one day saying, ‘You’re very well known.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Well, your tool is the recommended tool by ISIS,’” Cheng told FedScoop in an interview. “It was a wonderful endorsement from the wrong party.”

While there wasn’t one moment that caused the U.S. government to take PQC seriously, Cheng said the “biggest” turning point was the release of National Security Memo-10 — which OMB’s latest memo serves as guidance for implementing — in May. That’s when the largest U.S. companies in network security infrastructure and finance began reaching out to Post-Quantum for consultation.

Post-Quantum now offers a portfolio of quantum-ready modules for not only secure messaging but identity, quorum sensing and key splitting.

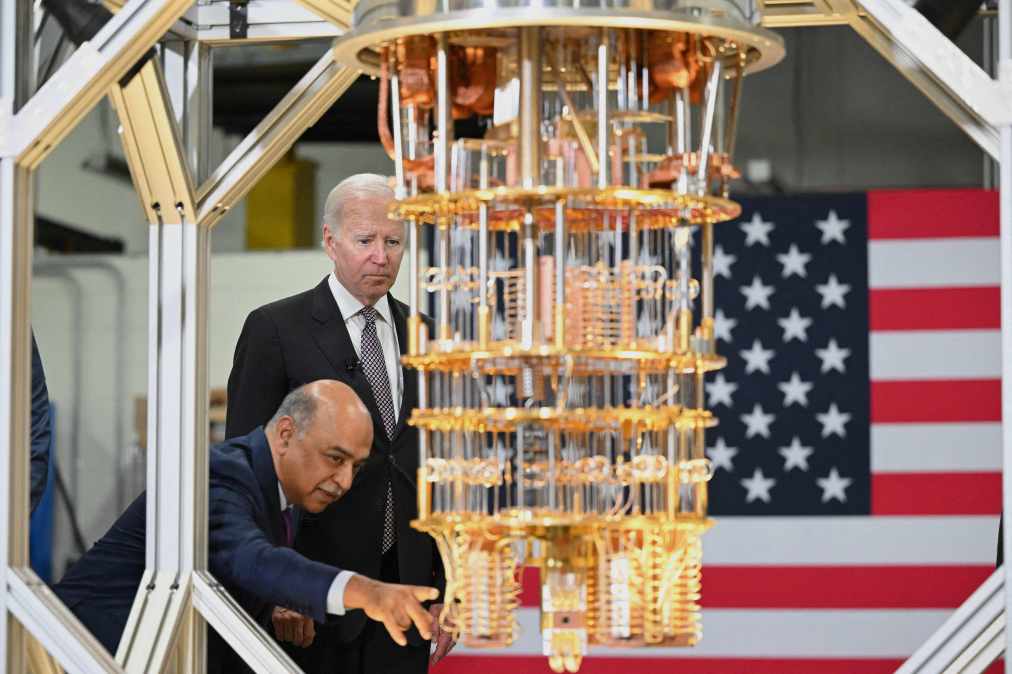

Cheng said the Quantum Computing Cyber Preparedness Act, sent to President Biden’s desk Friday, should become law given PQC’s momentum, but he has “slight” reservations about the OMB memo’s aggressive deadlines for agencies to declare a migration lead and to conduct an inventory audit.

“People are probably underestimating the time it will take because the entire migration — I’ve spoken to some very top-end cryptographers like the head of crypto at Microsoft and so on — our consensus is this is a multi-year migration effort,” Cheng said. “It will take 10 years, at least, to migrate.”

That’s because public-key encryption protects everything from Zoom calls to cellphones, and the National Security Agency isn’t yet recommending hybridization, which would allow for interoperability among the various NIST-approved algorithms and also whichever ones other countries choose. Agencies and companies won’t want to swap PKE out for new PQC algorithms that won’t work with each other, Cheng said.

Complicating matters further, NIST is approving the math behind PQC algorithms, but the Internet Engineering Task Force generally winds up defining connectivity standards. Post-Quantum’s hybrid PQ virtual private network is still being standardized by IETF, and only then can it be added to systems and sold to agencies.

Cheng recommends agencies not wait until their inventory audits are complete to begin talking to consultants and software vendors about transitioning their mission-critical systems because PQC expertise is in short supply. Large consulting firms have been “quietly” building out their quantum consulting arms for months, he said.

OMB’s latest memo gives agencies 30 days after they submit their cryptographic system inventory to submit funding assessments, a sign it won’t be an unfunded mandate, Sanzeri said.

“This is showing that all of federal will be well into the upgrade process, certainly within 12 months,” he said.