Agencies take cautious approaches to OPM email asking for list of accomplishments

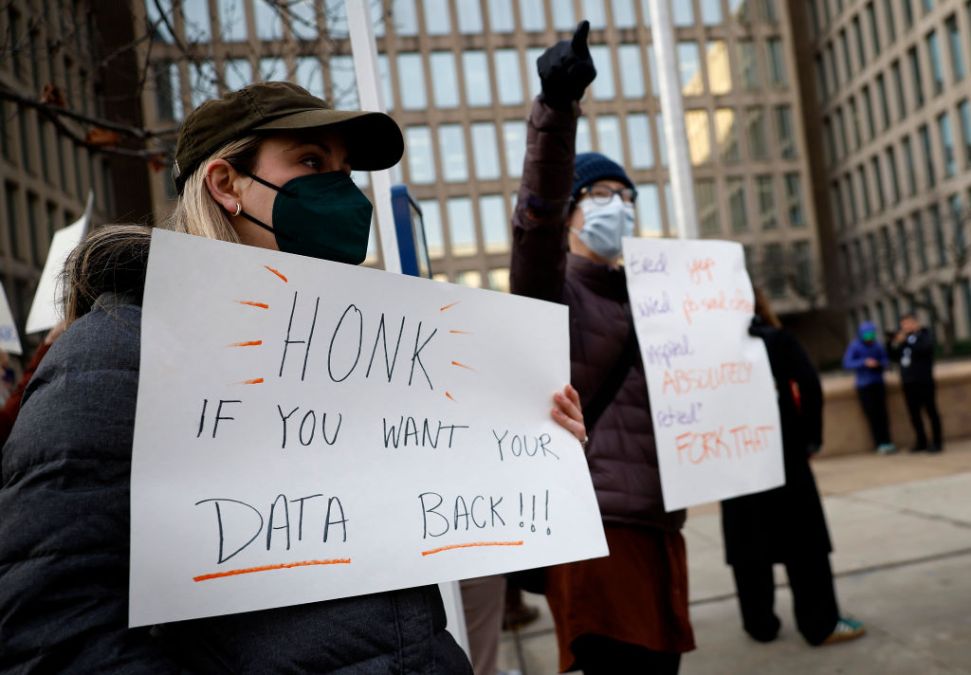

Government agencies responded with caution to the Office of Personnel Management’s request that federal workers provide five bullet points about what they accomplished last week by the end of the day Monday.

The Securities and Exchange Commission gave workers a template to follow; the General Services Administration and Department of Commerce told employees not to send classified information, links or attachments; and the Department of Defense told employees to pause responses for the time being, according to emails obtained by FedScoop and agency statements.

At least some agencies ultimately told employees participation wasn’t required. According to a Monday email sent to SEC employees that FedScoop obtained, leaders were told verbally by OPM that responding to the message was voluntary. Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Justice employees were also informed that responses weren’t necessary, per an HHS email viewed by FedScoop and a response from a DOJ spokesperson.

The varying agency approaches appear to reflect the sensitivity of certain government work, as well as concern for security and how the information will be used.

In the event employees chose to respond to the message, HHS went as far as telling workers they should “assume that what you write will be read by malign foreign actors and tailor your response accordingly,” according to the emailed guidance sent to employees Monday night.

SEC’s guidance instructed employees responding to the message to use a template it provided and fill in the five bullets using a list of options provided by the agency in an Excel spreadsheet, according to a copy of that email obtained by FedScoop.

“Given the non-public and sensitive nature of the agency’s work, SEC staff must not provide any additional information beyond the general template provided below,” the email from SEC Chief Operating Officer Kenneth A. Johnson said.

‘What did you do last week?’

The initial request from OPM came in the form of an email titled “What did you do last week?,” which arrived in the inboxes of federal workers over the weekend, per a copy viewed by FedScoop. That message asked each worker for roughly five bullet points about what they accomplished last week, told employees not to send classified information, and gave them a deadline of Monday at 11:59 p.m. to respond.

News that the email was coming was first announced on X by Elon Musk, a senior adviser to President Donald Trump. The X owner posted Saturday that the emails would be sent shortly and that “failure to respond will be taken as a resignation.” The prospect of termination, however, was not ultimately part of the emails sent to the employees. And the messages to employees in SEC and HHS, at least, specifically noted that not responding wouldn’t impact employment.

But late Monday confusion intensified when Musk and OPM sent seemingly conflicting guidance. Musk again posted to X at roughly 7 p.m. that “subject to the discretion of the president” employees would be “given another chance” and that “failure to respond a second time would result in termination.”

Meanwhile, in guidance sent to agency leaders Monday and posted publicly on the Chief Human Capital Officers Council website later that night, OPM told officials that it’s at the discretion of agency heads to exclude personnel from responding.

That guidance said responses to the “email should be directed to agency leadership, with a copy to OPM” and that agencies should be the ones to review responses and nonresponses. It also said employees on approved leave or don’t have access to email were not expected to respond by the deadline.

At a Tuesday press briefing, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt indicated agencies that told their employees not to respond aren’t in the wrong. “For some of the agencies that you’ve seen who have said ‘please don’t send these emails,’ it’s in their best interest for that specific agency and the president supports that,” Leavitt said.

OPM has not responded to FedScoop’s requests for comment about scope of the request or whether the expectations have changed since it was sent.

The human capital agency has taken on a large role in the Trump administration’s efforts to downsize the federal government. OPM first began by testing a governmentwide email capability so it could communicate with all federal employees in January. Later, it gave federal employees an option to defer their resignation from their roles in an offer it dubbed “Fork in the Road” and it allegedly directed agencies to fire their probationary employees.

Mulling over responses

The initial “five bullets” email from OPM began a scramble by agencies to figure out how and whether their employees should respond with many agencies coming to different conclusions.

SEC, for example, initially told its workers to wait for guidance before responding to the email, according to a message sent Saturday to employees that FedScoop obtained. HHS similarly told workers to pause their response to the message until guidance was sent, according to an agency source who was granted anonymity to speak more freely. That guidance eventually came late Monday.

Even agencies that were instructed to reply noted information that shouldn’t be sent. For example, GSA’s message specifically said not to include “any procurement sensitive information” in addition to its directions not to include classified details, links and attachments.

Nick Hart, president and CEO of the nonpartisan, nonprofit Data Foundation, told FedScoop that from a data perspective there’s more to a request like OPM’s than meets the eye.

“While it sounds like a very simple request to write a handful of bullets about what you’ve done, there are a lot of really important intersections with how the request relays information about individual employees, but also how that integrates with what is a fairly large data system at OPM,” Hart said.

For example, he noted that data principles outlined in the Federal Data Strategy advanced by the first Trump administration are relevant to the data collection effort by OPM. That includes concepts such as minimizing data the government is collecting about the American people and ensuring that the purpose of federal data will be useful, he said.

There are also typical practices before a request of that kind is made — particularly when it imposes a burden on the American public — to ensure questions are reviewed, that the right formats and methods are being used for collection, and that the information can be protected, Hart said.

“I think that the challenge for an agency, and actually every individual responding to any kind of data collection, is really piecing all of those parts of a complex puzzle together,” he said. “But our goal is high-quality information that can be used.”

Collecting human capital information also has security risks, particularly given that the human capital agency has in the past been a victim of cybercriminals.

Fred H. Cate, a law professor at Indiana University focused on information privacy and security, pointed to the 2015 OPM cyberattack that targeted government security clearance files and compromised the information of roughly 22 million people. U.S. authorities accused the Chinese government of the attack, though Beijing claimed the hackers were criminals acting on their own.

Getting people to describe their jobs and putting them in one place “looks like a classic Chinese attack,” Cate said. He noted that Chinese cyberattackers are known for trying to build databases of people who work for the government and their roles, which is likely why the OPM attack took place.

“It’s not an agency, even under the best of times with seasoned leadership, that totally fills one with confidence about its handling of secure information,” Cate said.

FedScoop’s Matt Bracken and Rebecca Heilweil and DefenseScoop’s Brandi Vincent contributed reporting.

This story was updated Feb. 25 to include additional details about Musk’s posts, the guidance from OPM, Leavitt’s comment, and comments from Cate.