Pentagon shares new vision to address problems with its microelectronics supply chain

The Pentagon released a broad “Microelectronics Vision” this week that outlines the foundational framework for its highly anticipated, in-the-making national strategy to help holistically mitigate intensifying supply chain vulnerabilities. However, some observers found it lacking in detail.

The 12-page document — publicly shared Wednesday by Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks via tweet — was informed by a range of comprehensive studies. It comes roughly a year-and-a-half after the Pentagon established the Defense Microelectronics Cross-Functional Team (DMCFT) to produce an enterprise-wide strategy with implementation and transition proposals to enable a more sustainable national ecosystem of such components, which are critical for a wide range of U.S. military systems.

“The U.S. military advantage depends on microelectronics to create and sustain technological superiority,” Pentagon spokesperson Lt. Cmdr. Tim Gorman told FedScoop on Friday. “Releasing the document now emphasizes the importance in developing a departmentwide microelectronics strategy.”

This vision includes a list of seven “interconnected objectives” to guide the overarching development going forward — though current and former Defense Department officials acknowledge that it’s somewhat vague in terms of execution.

The objectives are:

- Ensure timely access to measurably secure and affordable microelectronics (ME) technology.

- Motivate programs and their primes to modernize and exploit the most capable ME.

- Leverage tools, policies and enforcement to reduce or eliminate costly sustainment issues.

- Centralize knowledge in a DOD “frontdoor” organization to augment decentralized execution.

- Increase ME discovery and innovation, and accelerate transition into DOD systems.

- Contribute to and influence interagency and national efforts to grow ME capabilities to meet national security needs.

- Cultivate a workforce with the right capacity and the right skills at the right place and the right time.

‘A pivotal moment’

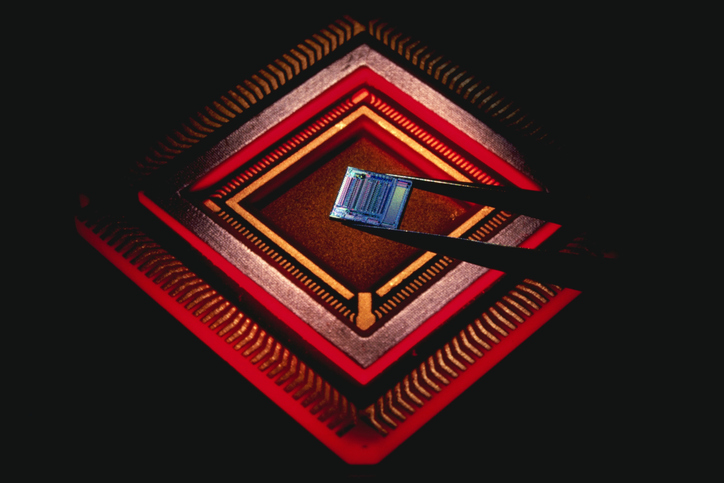

Microelectronics like semiconductors or chips are embedded in a slew of platforms the Pentagon buys and relies on — from mobile communications devices to computers, advanced weapon systems, and more.

“Each of the Javelins you produce includes more than 200 semiconductors,” President Biden recently told employees at a Lockheed Martin missile factory in Alabama. “The semiconductor is critical to defense production capacity.”

But the United States has struggled to enable a secure domestic production base for military-related chips for decades. And experts are tracking a range of factors that have persistently hindered DOD’s access to chips for military and other mission-specific applications.

“Depending on the program, a fundamental challenge is that in many of our weapons systems, we are not using the most recent, most powerful, and most capable chips. We’re using what they call ‘legacy chips,’ which are much less robust, although not necessarily ineffective. We talk about the latest Apple iPhone, but we run our airlines and our banking systems and our Defense Department in large part using legacy systems,” Charles Wessner, a research professor at Georgetown University and non-resident senior adviser for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told FedScoop on Thursday.

The Pentagon’s needs and access to microelectronics continue to evolve. For many reasons, most semiconductors are currently produced by foreign suppliers — and a global supply chain shortage, intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic and other challenges, is forcing the Pentagon and the nation writ large to confront major disruptions.

In response to this ongoing shortage, Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Heidi Shyu has elevated microelectronics as a top priority and critical technology area for DOD. The department is also investing heavily to boost domestic manufacturing. Further, the White House and senior federal officials are simultaneously urging lawmakers to quickly pass the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) legislation, which would direct billions of dollars in funding toward efforts to strengthen America’s microelectronics production.

“The most important thing that can be done right now is that the Congress can pass the American Innovation Act, the CHIPS Act, to get us on-shored here in the United States microchip processing capability, manufacturing and processing capability,” Hicks said this week.

Still, many of the issues this new prioritization of microelectronics aims to address have been bubbling for a while.

“It’s very encouraging to see that they’re focused on this crucial component of our armed defense systems,” Wessner said of the new microelectronics vision. “It’s a very valuable initiative. It’s certainly not too late, but it needs to be done.”

In the document, Shyu and Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Bill LaPlante wrote that the DOD “is at a pivotal moment where it must take advantage of the national interest and funding in [microelectronics] by developing a unifying vision and strategy to ensure national security equities are met.”

The vision, which could be refined and updated over time, is a product of recommendations from the DMCFT, they noted.

Gorman confirmed the DMCFT has been engaging with subject matter experts from across the private and public sectors and reviewing heaps of materials to inform their crafting of this early document and the official strategy that will follow.

That team was formed in early 2021 to address six vulnerabilities associated with procurements of critical microelectronics components that fundamentally threaten DOD’s ability to sustain and buy key weapons, following a deep examination of the world’s and department’s supply chains in 2019 and 2020. So far, they have developed a “central vision statement,” which says DOD will “obtain and sustain guaranteed, long-term access to measurably secure microelectronics that enable overmatch, increased operational availability, and support warfighter combat readiness.

Gorman said: “The DMCFT is using this vision to identify approaches and resourcing requirements to achieve the department’s strategic microelectronics objectives. The DMCFT will continue to collaborate across the interagency, industry, and academia in developing the DOD implementation and transition plans.”

Questions remain

“I would like to see DOD proposing something more concrete,” Bryan Clark, senior fellow and director of the Center for Defense Concepts and Technology at the Hudson Institute, said of the Pentagon’s new microelectronics vision document.

“The vision is a little disappointing. We need a strategy, but that implies a document that describes the choices and priorities DOD will establish and how it will pursue them,” Clark told FedScoop on Thursday. “This vision identifies a set of objectives without any sense or prioritization or mechanism to accomplish them.”

Clark, who served in several federal roles including special assistant to the chief of naval operations after retiring from the Navy, added that a complete strategy “would identify how DOD would like government funding to be prioritized” in existing and future initiatives, and describe “how the department will incentivize industry to modernize the microelectronics in their systems.”

The vision includes brief “objective alignments” that elaborate on the department’s approach — though they are each pretty vague.

For example, the vision states that the Pentagon “will ensure that programs and primes have the resources, motivations and know-how to utilize relevant ME technologies, processes standards and support” — but does not hint at what those incentives might look like.

“A challenge DoD faces is that most defense systems use older types of microelectronics and therefore they don’t exploit the advancements happening in commercial or research applications such as small node sizes, chiplets, [system-on-a-chip], etc. DOD wants industry to move into new generations of chip technology because they offer more functionality, but also because they can gain from private sector investment in innovation. Incentivizing this shift will mostly involve changing requirements to demand more sophisticated chip designs in DOD systems, which may cost more,” Clark said.

Wessner also noted in a separate conversation: “The question will be, what are the incentives in place?”

Gorman declined to provide any specifics regarding plans to “motivate programs and primes” to exploit microelectronics, among other inquiries this week.

Clark added that the vision argues for on-shoring, or shifting capabilities to be domestically produced, to make the microelectronics supply chain both more resilient to shocks and more secure against tampering.

However, “tampering can occur regardless of where the fabrication, packaging, or testing is done, and DOD should be accelerating its move toward ‘zero-trust’ microelectronics where testing catches alterations that are meaningful,” he said. “In terms of resilience, allies like Japan, Korea, European countries, and Canada can build more microelectronics of the types DOD needs. This ‘near-shoring’ could address the concern as well as bringing capacity back to the U.S.”

In Wessner’s view however, the document — while not as concrete as some would like — does incorporate “an encouraging amount of detail” for an initial vision statement.

“You have endorsement at the top of the department. Yes they’ll have to execute. Yes, it will be difficult — but you get there by starting,” he said.

He added that this work needs to continue to have sustained resources, high-level attention and “some ability to break through the compartmentalization that often creates challenges for the department’s acquisition teams.”