The Library of Congress finally finished its quest to digitize the original Lincoln documents

Digitization is a “very laborious and time-consuming process,” as Tim Stutz will be the first to admit.

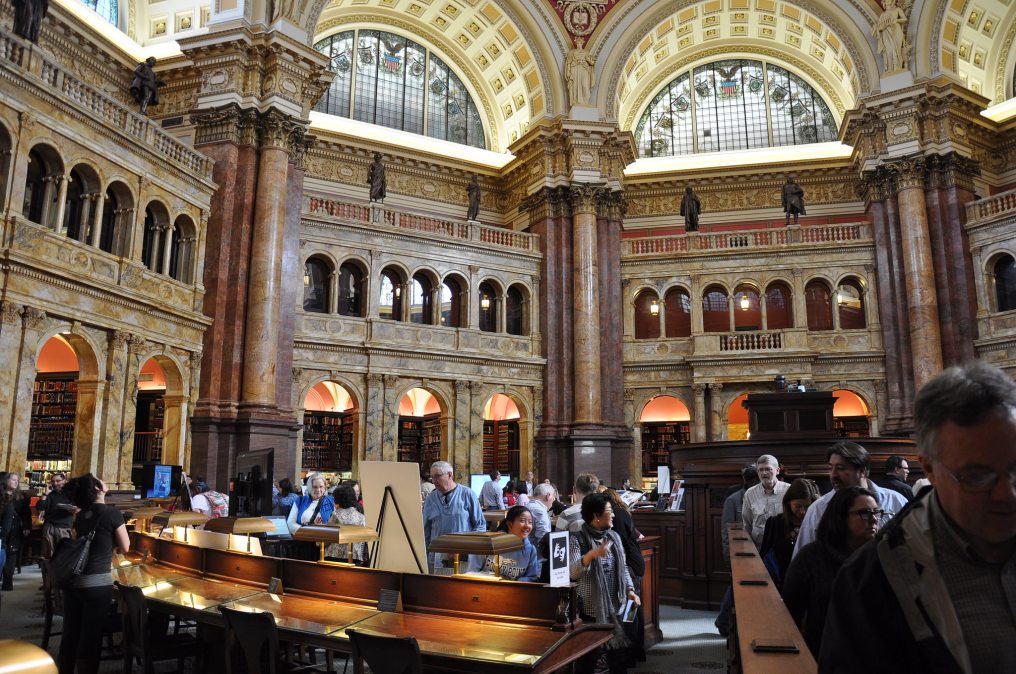

A digital conversion specialist at the Library of Congress, Stutz has spent the past nine years working on an updated trove of Abraham Lincoln’s papers. The collection includes Lincoln’s inaugural address, a draft of the Gettysburg Address and more than 20,000 other original documents from Lincoln’s life and presidency.

It’s not the first time many of these documents have graced the internet — in 2001 the Library first posted microfilm versions of the papers online. This is how the library gets most of its old documents onto the internet, with the advantages of not damaging the original and being relatively cheap.

The collection was extremely popular, the library says, but it had the disadvantage (for serious historians, etc) of being low resolution and in black-and-white. So in the early- to mid-2000s, the library started thinking about working to post high resolution, one-to-one ratio scans of the original documents.

This presented some challenges — chief among them the issue of how to scan originals without damaging them.

So how’d the Library of Congress do it? Turns out, with a camera.

Instant capture technology has improved a lot since 1998, said Dominic Sergi, head of the library’s digital scan center. It’s also gotten cheaper.

For this collection Sergi used a 70 megapixel camera to capture the documents in just two seconds. This is a marked improvement over the old method of scanning these documents, which involved a scanner that took three to five minutes per page.

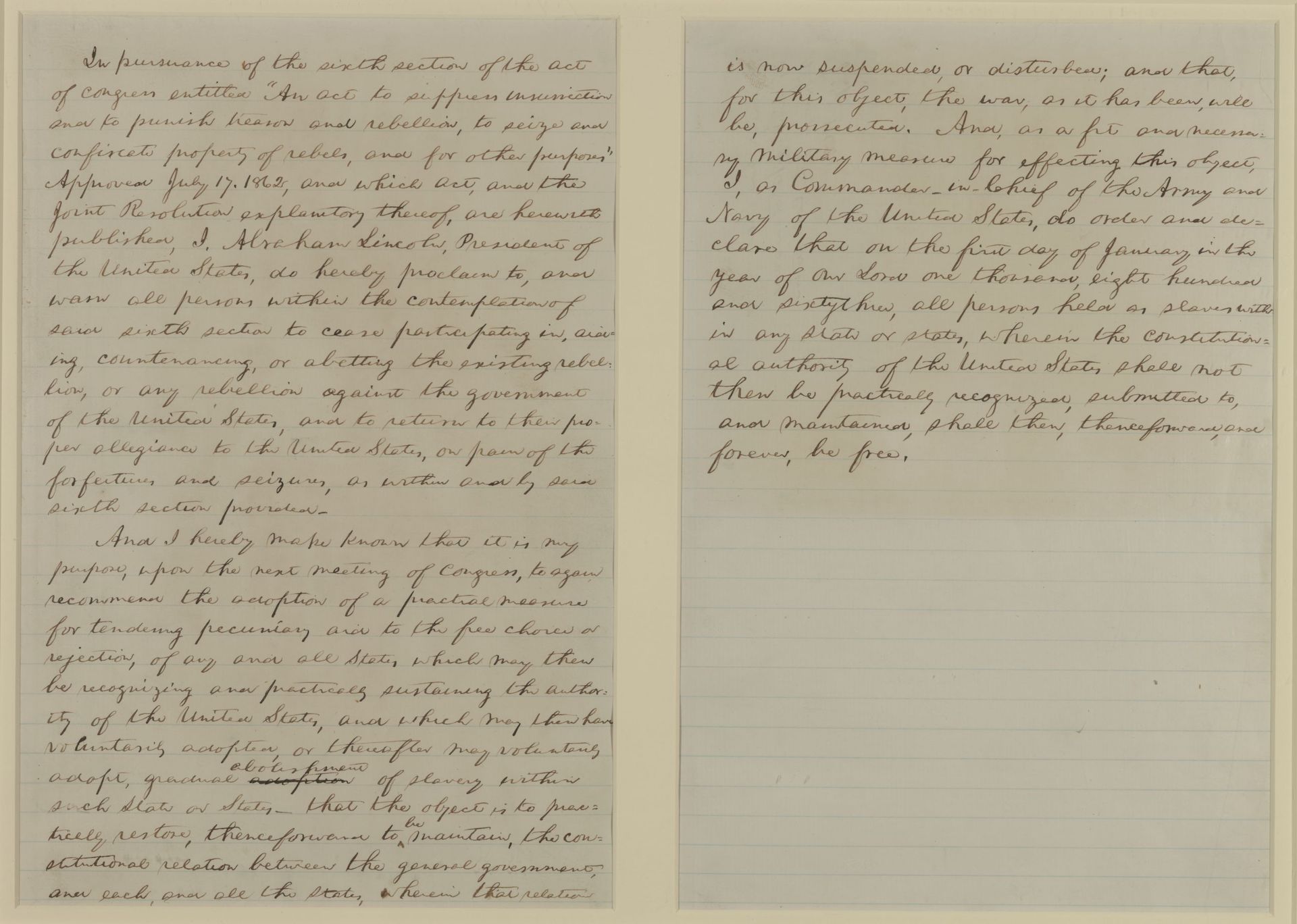

A draft of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, as seen in the new collection. (Library of Congress)

For Stutz this means a quicker time to the next stage of the digitization process — quality assurance, tagging, collating and more. Despite the speed with which the images were captured, though, the whole process remained lengthy. It took six years, Stutz said, to replace all of the microfilm images online with new and improved color images.

So why bother?

For the Library of Congress, it’s all about the accessibility of the documents. With the microfilm copies, researchers lost details like handwriting, color of the paper and more. But with the full-color scans, they’ll be able to appreciate such things. An incremental development but an important one, the library says.

“The thousands of manuscripts, documents and images that tell the story of Abraham Lincoln’s life are an invaluable resource, and more people than ever can study these primary sources from the Library of Congress,” Carla Hayden, librarian of Congress, said in a statement.

And so marches the development of technology — slowly toward a slightly more user-friendly product.