The Department of Homeland Security last year deployed a multi-million dollar electronic health record system to provide end-to-end health care services for the tens of thousands of illegal immigrants currently held in DHS detention facilities. But a new report by the health arm of the National Academy of Sciences shows the department has largely failed to provide its own employees in high-risk jobs with even the most basic health services and has yet to deploy an electronic system capable of capturing information on employee health, safety and readiness.

The report, “Advancing Workforce Health at the Department of Homeland Security: Protecting Those Who Protect Us,” is the work of a committee of more than a dozen health care experts from the Institute of Medicine. It paints a picture of an agency struggling to develop an enterprisewide health management system capable of collecting and analyzing health data for the 200,000 DHS employees scattered across the country, oftentimes in remote border locations.

“This capability currently does not exist at [the Office of Health Affairs] or anywhere else within the department,” the report states.

Although the report applauds efforts made by individual component agencies within DHS, particularly the Coast Guard and the Transportation Security Administration, it faults the department for failing to create a knowledge management system capable of collecting health information from each of the component agencies that make up DHS and providing senior leaders with the tools necessary to coordinate and monitor health, safety and readiness across the department.

“Workforce health protection and medical services programs vary significantly across DHS, with little coordination and integration,” the report states. “The result has been preventable morbidity and mortality, avoidable liabilities, and inefficiency.”

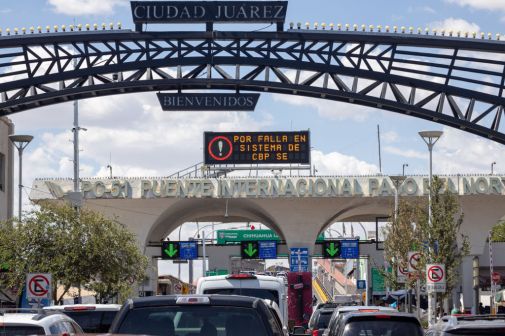

But for employees of Customs and Border Protection, the lack of an integrated electronic health care system has posed more significant challenges. While CBP officers have been working around the clock to counter the more than 60,000 unaccompanied minors who have been apprehended on the southern border so far this year, “stovepiped programs and lack of communication and coordination mechanisms across DHS have resulted in failures of knowledge management” that have led to some CBP officers not receiving the same health care services provided to illegal detainees.

In one example, CBP’s occupational safety and health office had conducted a cost-benefit analysis of placing medical clinics or practitioners at some of its high-volume stations along the southwest border to help manage employee injuries and illnesses. But the agency determined that employee utilization rates would not be high enough to justify the costs. Unknown to CBP, however, OHA had conducted a similar cost-benefit analysis indicating that significant cost savings could be achieved by having on-site medical care for detainees at high-volume Border Patrol stations. “These estimates did not even include collateral benefits to employees. Remarkably, neither office had been aware of the other’s efforts,” the report states.

In and email to FedScoop, a DHS spokesperson said the department understands the importance of a healthy workforce and continues to make efforts to build a robust health and medical infrastructure across the department. In fact, some of the issues mentioned in the report have been independently identified by DHS and the agency has taken steps to address them, the spokesperson said.

“OHA recently hired an Occupational Health physician to focus on DHS-wide medical readiness information and policy,” the spokesperson said. In addition, an effort to embed senior medical officers to standardize and streamline the department’s health activities is “is expanding and ongoing,” the spokesperson said. “The department is closely looking at the recommendations and working on additional, appropriate actions to further enhance the health, safety, resilience and mission readiness of our workforce.”

CBP maintains a large cadre of emergency medical technicians, including about 200 highly-trained search and rescue agents who hold medical certifications. But there is an acute lack of EMTs available for non-emergency medical care along the border. According to the report, this is due largely to the drain on resources stemming from the current border crisis. In fact, a study by OHA found that CBP dedicates approximately 90,000 agent-hours per year to escorting illegal detainees to emergency rooms or other medical facilities before they can be transferred to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The nearest emergency room is often located hours away.

“A comprehensive operational medicine program addressing the health and medical needs of detainees in addition to those of DHS employees could have significant mission impacts,” the report concluded.

The example of CBP is instructive as it demonstrates the drawbacks of not having an enterprisewide view of health care trends and issues in an organization as large and complex as DHS. But challenges like those experienced by CBP personnel date back as far as 2004, when former Secretary of Homeland Security Tom Ridge ordered a review of DHS’ medical readiness. That review, according to the IOM report, found “workforce health programs were fragmented and implemented unevenly across components, lacked visibility and authority, and were inadequately staffed.” And many of those deficiencies have yet to be corrected, the report said.

DHS has the highest rate of occupational injury and illness of all cabinet-level federal agencies, and CBP has the highest rate of any federal agency. In fiscal year 2011, the actuarial liability for workers’ compensation at DHS surpassed $2 billion — 4.4 percent of the department’s overall appropriation.

But IT systems used at the component level to manage and track worker compensation data and other occupational health and safety information vary widely, preventing the data from being aggregated and analyzed at DHS headquarters, according to the IOM report.

“Some components use spreadsheets to track this information, while others, such as TSA, have sophisticated safety information systems that track reported injury/illness and workers’ compensation claims, as well as leading indicators such as information from safety inspections and job hazard analyses,” the report states. “Although DHS is moving toward an enterprise approach to HIT, the committee did not find evidence that the department is fully aware of the informatics capability required to maximize the potential of an integrated health information management system.”

DHS is in the process of acquiring a departmentwide electronic health information system, but funding has not yet been approved.